Researchers in France have used their knowledge of the way a human acquires language to create a robot "brain" that listens and understands language using recurrent construction. This gives the robot the ability to decode complex sentences quickly by predicting what follows from each word, and then modifying those predictions from context as new words are spoken. Humans process language in real time, and our brains execute loops of understanding -- as I grasp it, it sounds like we narrow down all possible meanings as each subsequent word comes to us, until the end of each sentence or phrase, where we've narrowed it precisely.

Of course scientists put this brain into the ridiculously baby-faced and disconcertingly man-voiced iCub robot. Here you can see it understanding the researcher's utterance. In this video the blue object is referred to as a guitar and the red object as a violin. Romantic, isn't it?

They made the robot better. That's fantastic. But here's the fascinating thing. As they make the robot's brain work like the human brain, they get a better understanding of the human brain. In the same way that we learn more about what it means to send the signals and impulses that make us bipedal and make our hands work, we understand more about how our brains actually think about abstractions and meanings by creating robots that think about abstractions and meanings. So these scientists are learning about how we lose function with Parkinson's, or how we gain control of this function as infants, by studying the simulation. They study the simulation to learn about the original.

Really, it makes sense. This terrifyingly complicated and mysterious thing we have in our heads -- the brain -- cannot be understood yet as a piece. We can't map it much, or see the whole thing working. I say terrifying because it boggles my (mysterious) mind that one of the most profound unknowns in all of biology or philosophy is our own self-awareness, our ability to know the things we *do* know. We look back at those silly Egyptians and the way they vacuumed the brain out and discarded it after death because it was useless, while lovingly preserving the spleen and liver. Well, I need my liver too. And how much farther along now are we, really? We know the brain is useful for something, right? Now we know how to make a brain that understands and decodes language in the same way we do. Thanks to his robot brain, we know more about ourselves.

Maybe that's the biggest reason to keep making better and better robots -- they help us understand ourselves, where we stop and machines begin, where that line is blurry and where it overlaps. Something to ponder if you watch the video: Parents, how many times have you asked your human child to repeat instructions back to you, so you know they're understood? Just like the robot does, and for the same reason. Your kid might not have a creepy man voice (yet) but here's a small way he's just like a robot all the same.

Pages

▼

Wednesday, February 20, 2013

Wednesday, February 6, 2013

Gödel, Escher, Bach: Introduction

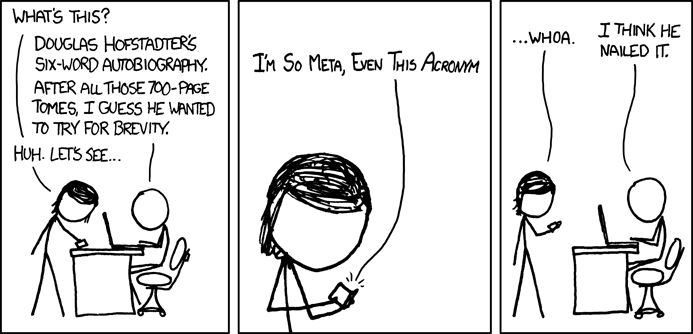

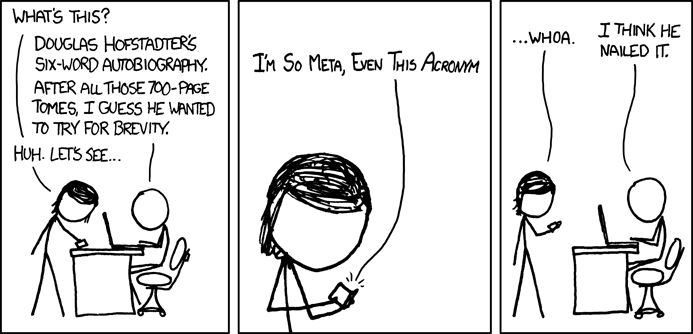

I have to start out this installment with a comic from xkcd, found by a guy in our Facebook reading group:

Yep, nailed it. Our group discussion wandered through self-referential words and the difference between a fugue and a canon, and landed on Gödel's Incompleteness Theorem, which no one really claimed to fully understand, but lots of us wrestled with. Here are some resources and links we found helpful, and my thoughts on the three sections:

Bach:

I really loved the Bach section -- it was so interesting to learn about how these musical compositions really begin with math problems, and how composers would set challenges for each other that could be solved mathematically. The anecdote about Bach sitting down to extemporaneously compose such a complicated canon for the King of Prussia was almost unbelievable, but I'm willing to swallow it. Then again I was a Lance Armstrong supporter for years. Maybe I'll believe anything of someone I want to be brilliant.

Here's a recording of that six part fugue, RICERCAR:

Here's a video of Bach's never ending canon, which rises in a "strange loop," mentioned on page 10:

Escher

I found the concept of "strange loop" easiest to understand visually, in Escher's work. Here is a link to a large image of Escher's "Waterfall" and also a video of Metamorphose, by Escher, hanging in a post office:

Gödel

I fell off the book backward at the Incompleteness Theorem, I'll admit. I was helped by several different ways of looking at it, including this post. Here's an interesting discussion of Gödel, by Stephen Hawking, called "Gödel and the End of the Universe."

I loved the stuff about Ada Lovelace and early computers. Was intrigued by predictably intrigued by L'Homme Machine, enough to buy a used copy in the French. The strange loops elude me at this point, but I think all of us in the group are hoping to understand the mathematics parts more fully as we go along. Comforted by the fact that "This is only the introduction!" we persevere.

Yep, nailed it. Our group discussion wandered through self-referential words and the difference between a fugue and a canon, and landed on Gödel's Incompleteness Theorem, which no one really claimed to fully understand, but lots of us wrestled with. Here are some resources and links we found helpful, and my thoughts on the three sections:

Bach:

I really loved the Bach section -- it was so interesting to learn about how these musical compositions really begin with math problems, and how composers would set challenges for each other that could be solved mathematically. The anecdote about Bach sitting down to extemporaneously compose such a complicated canon for the King of Prussia was almost unbelievable, but I'm willing to swallow it. Then again I was a Lance Armstrong supporter for years. Maybe I'll believe anything of someone I want to be brilliant.

Here's a recording of that six part fugue, RICERCAR:

Here's a video of Bach's never ending canon, which rises in a "strange loop," mentioned on page 10:

Escher

I found the concept of "strange loop" easiest to understand visually, in Escher's work. Here is a link to a large image of Escher's "Waterfall" and also a video of Metamorphose, by Escher, hanging in a post office:

Gödel

I fell off the book backward at the Incompleteness Theorem, I'll admit. I was helped by several different ways of looking at it, including this post. Here's an interesting discussion of Gödel, by Stephen Hawking, called "Gödel and the End of the Universe."

I loved the stuff about Ada Lovelace and early computers. Was intrigued by predictably intrigued by L'Homme Machine, enough to buy a used copy in the French. The strange loops elude me at this point, but I think all of us in the group are hoping to understand the mathematics parts more fully as we go along. Comforted by the fact that "This is only the introduction!" we persevere.